A year after the Licensing of the Press act finally lapsed in 1695 Mr Edward Lloyd, coffee-house keeper in Lombard Street, London, had a news letter printed for the benefit of his customers. It depended on the same news sources as other newspapers of the time but his name was on the masthead. Lloyd’s News was, however, shortlived. On 23 February 1696/7 this item appeared in it:

Yesterday the Lords passed the Bill to restrain the Wearing of all wrought Silks from India, with this amendment, to Prohibit the Importation of them from all Parts, which they sent to the Commons for their Concurrence. They also received a Petition from the Quakers that they may be freed from all Offices.

Three days later Ichabod Dawks’s Protestant Mercury reported (with a smirk, one imagines) that the Lords had demanded a correction, on the grounds that the Quaker item was untrue. Lloyd (taking the Murdochian option) abruptly closed down his paper instead, saying the line had been added by the printer. Nonetheless, a Quaker petition to the Lords did exist.

On 22 February the House of Lords passed a bill to prohibit the wearing and importing of Indian silks, a matter on which minds, both mercantile and parliamentary, had been concentrated following a tumultuous march by Spitalfields weavers on Westminster and the East India House a month earlier. The same day another bill came to the Lords from the Commons, against the buying and selling of offices, and during the week they heard petitions on that bill and a third, the prisons and pretended privileged places bill.[1] This last was intended to shut down lawless debtors’ sanctuaries such as Whitefriars; the Quakers feared it would add to their risk of imprisonment for non-payment of tithes, despite a recent act which allowed for a levy to be taken on their property instead.

The connection with offices was oblique. Quakers were barred by their religion from holding any of the lucrative government-controlled offices, however they had previously published a broadside arguing on ethical grounds against the buying and selling of them. What did concern them directly were elected parish offices such as churchwarden, which were obligatory, time-consuming and, for Quakers, perverse since they were concerned with the religious management of the parish as well as the secular. They could be side-stepped by payment of a fine, but the payment – or not – of tithes for the maintenance of the clergy was a separate matter.

Who was the printer in question? The paper itself is silent on this. Lloyd’s News was not Edward Lloyd’s first publishing venture. Until 1691 his coffee-house had been in Tower Street, near the Custom House quay where ships were loaded and unloaded. His new address was a few minutes’ walk from the Royal Exchange where merchants conducted business; a stroll from the quay to the Exchange would have brought them past his door. Around the time of the move he had introduced a printed list, Ships Arrived at and Departed from several Ports of England, as I have Account of them in London … An Account of what English Shipping and Foreign Ships for England, I hear of in Foreign Ports, which he continued to publish after shutting down Lloyd’s News, until 1704 or later. He was also selling shipping intelligence to at least one joint-stock company.[2] It is possible that he launched these lines of business back in Tower Street, but now he was almost next door to the General Post Office, where he may have arranged for preferential treatment of his mail.[3]

Surviving issues of Ships Arrived and Lloyd’s News carry only the imprint of Edward Lloyd as publisher. As for the unnamed printer, there are possibilities nearby. Leading off Lombard Street was an entry to the Quaker meeting house in White Hart Court, Gracechurch Street, and another to Three Kings Court which housed the central repository of Quaker books; across the road on the north side of Lombard Street there were Quaker businesses in George Yard. These were the places where Quaker booksellers had their shops; one of them at least was also a printer.

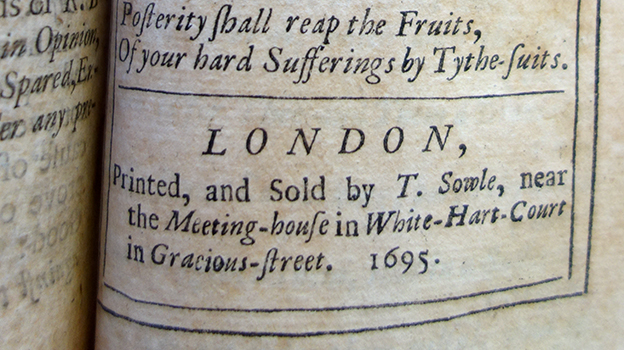

Next to the White Hart Court meeting-house was a bookshop belonging to a woman by the name of Tace Sowle. At about the time Lloyd moved to Lombard Street she had started to run her ageing father Andrew Sowle’s printing and bookselling business. That was unremarkable; numerous seventeenth-century women ran family businesses, usually in their widowhood. Work premises were also the places where the family lived with their apprentices, and there is a glimpse of domestic arrangements in some evidence given by a printer’s man in a 1664 treason trial: he brought proof sheets from the work-house into the kitchen and laid them upon the dresser to be corrected.[4]

Tace, however, was more than a manager; she had been apprenticed to her father, and was said to be a good compositor.[5] She was equally unusual as a woman who built up the strength of the business rather than simply maintaining it. Her father had inclined to otherworldliness about money, and when she took over from him one of her first actions was to get the Friends’ help in chasing long overdue payments; over the next few years she also vastly increased the output of the press.

From their beginnings Quakers had maintained the view that women could be preachers; many were, and Tace published them. While she herself did not preach she had in her hands a more potent means to influence and instruct. She was formally approved by the Friends’ leadership as their printer, and as a proselytising sect they understood the power of a well-managed press operation. She also advised them on effective publishing strategies. The other names chiefly associated with Quaker printing in her time, Benjamin Clark (likewise approved), his ex-apprentice Thomas Northcott and Thomas Howkins, were almost certainly not themselves printers, but operated solely as publishers and booksellers.[6] Tace was all three, and her output was not limited to religious publications; like her father she printed manuals and treatises on practical subjects – health, household management, education, economics – that mattered to the self-reliant Quakers.

Is there a case for Tace Sowle as Edward Lloyd’s printer in 1696–7, and the author of the news item that the Lords objected to? She certainly had one foot outside the confines of the Friends, in the world of the merchants who were Edward Lloyd’s customers. Her bookshop was along the street from his coffee house. Advertisements for stationery for sale in the shop include bills of lading – shipping forms that would also have been used in her own business, which shipped books overseas in great quantities. Like her father, she printed books by the ruthlessly acquisitive East India merchant Sir Josiah Child, decidedly no Quaker, and a little later she was printing broadsides for the Post Office advertising a new packet-boat service between Bristol and New York. She had just become formal head of her father’s press, and was evidently flexing her muscles as a printer and publisher. It was the practice of the Friends to deliver their polemical papers by hand directly to parliament, and as for the decision to tack their case onto a news story: if not Tace, who else?

Those arguments assume it was a Quaker printer who added the line in Lloyd’s News. But it seems to mix up three separate issues: the trading of government offices, the Friends’ long-wanted exemption from tithes and the burden on them of parish offices. Intentional or not, that would be untypical of a literate Quaker, if less surprising in an apprentice. A more likely explanation is carelessness (or mischief) on the part of an unknown news writer employed by Lloyd. He seems to have concluded that running a newspaper was more trouble than it was worth.

Lloyd evidently positioned his ill-fated News to appeal to a coffee-house patron higher up the proprietorial scale than the underwriters who scanned the lists printed in Ships Arrived. Unlike contemporary newspapers Lloyd’s News was designed to have the feel of a handwritten news letter, set in a single column in a large italic type on heavy paper. The type itself is interesting, being very like an English italic cut by Peter van Walpergen for John Fell’s press at Oxford University, though not quite identical. While that may be useful in trying to identify the printer of Lloyd’s News, it more or less rules out the chance that the sheet came from Tace Sowle’s press, where the letters are not seen.[7]

There is, nonetheless, one sure connection between Tace Sowle and Edward Lloyd. The two earliest extant copies of Ships Arrived are from 1696 and 1698 – they survived by chance among the office paperwork of a merchant from Hamburg who had premises off Threadneedle Street[8] – and the latest is from 1704, but the paper could have continued for much longer. Lloyd died in 1713; within a year or two Tace Sowle had moved her press from Leadenhall Street into George Yard, Lombard Street, at the sign of the Bible. By the 1730s if not earlier an evolved version of Ships Arrived was appearing under the title Lloyd’s List, published by Lloyd’s successors at the coffee house. The earliest known extant issue is no. 560, from 1740/1; the earliest with a printer’s name is from January 1743/4, and the printer is Luke Hinde in George Yard, Lombard Street.

Luke was Tace’s great-nephew; his father Andrew (son of her sister Jane by her first husband) had been apprenticed to Andrew Sowle. Luke was freed by patrimony, and by 1736 was Tace’s partner at the press. On her death in 1749 he inherited the business, and continued to print Lloyd’s List alongside Quaker publications. To print accurate twice-weekly shipping news would have required an efficient publishing operation. Hand-written lists from the ports were brought in by post boys to the General Post Office; by the following day they had been edited, printed and put out in the coffee house. That the printer was local seems likely, and it is possible that Lloyd’s List was printed in George Yard from much earlier, maybe even from its beginnings as Ships Arrived.

As a whodunnit this story is unsatisfactory. Who provoked that small incident in newspaper history remains unanswered, possibly unanswerable. Just as interesting though, and going largely unnoticed, is the fact that the bread-and-butter work which sustained the vast religious output of Tace Sowle’s celebrated printing house was Edward Lloyd’s yet more celebrated marine list. The two worlds, or at least their historians, seem to be no less separate now than they were three centuries ago. For 20 years from 1692 these two individuals could have passed each other every day on Lombard Street; at some point the two houses also began to do business with each other.

For the origin of the name Tace see this post.

Notes

- ‘An Act to prevent the buying and selling Offices and Places of Trust’, and ‘An Act for the more effectual Relief of Creditors in Cases of Escapes, and for preventing Abuses in Prisons and pretended Privileged Places’. Some petitions are noted in Journal of the House of Lords; petitioning against the sale of offices was also reported by The Post Man [no. 282, 25–27 February 1696/7].

- In 1693 the Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company paid ‘Mr Lloyd the Coffeeman’ £3 for intelligence of the Company’s ships. Vol. XXI, Hudson’s Bay Record Society, quoted in Bryan Lillywhite, London coffee houses, 1963.

- There is a substantial account of Edward Lloyd and his various operations in Charles Wright & C. Ernest Fayle, A history of Lloyd’s, 1928. John J. McCusker, in Essays in the economic history of the Atlantic world, 1997, p. 113, suggests that the the special arrangements the Lloyd’s List publisher is known to have had with the Post Office during the eighteenth century could have begun in the 1690s.

- The trial of John Twyn in 1664, in A complete collection of state-trials and proceedings for high-treason, 3rd edn, vol. 4, 1742, p. 532

- By the printer John Dunton who described her admiringly in The life and errors of John Dunton, 1705.

- Clark’s name in publishing imprints appears almost invariably in the formula ‘printed for Benjamin Clark’, as do Howkins’s and Northcott’s, implying that they put out their titles to the trade to be printed. As in Tace Sowle’s books, the imprint or colophon occasionally takes the form ‘printed, and sold by — at —’, sometimes without the comma. The address given was the place where the book was for sale; the identity and location of the printer was seldom disclosed, except by Tace who was her own printer. She may also have put work out to be printed.

- Nearly all surviving issues of Lloyd’s News are in sole copies held by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Nichols Newspapers, vols. 9b and 9c.

- National Archives, Kew. Matthias Giesque & Co Papers, C.104/128, part 2