On 22 February 1665 Richard Watts, a notary at Deal in Kent, sent an anguished complaint to John Carlile, an official at Dover, against the Deal postmaster Morgan Lodge:

When I carryed my letter to the Post Office: Lodge very much abused mee before severall, & would not take my letter unless I set the date on the out side : And when I went into the office to doe it, hee told mee I was a lying knave (without ainye provocation) I asked him wherein, & if hee did not tell mee in what he was a lyer ; then he struck mee & thrust mee out, & sayd I should not come into the office, and asking for my gloves, hee took my gloves and threw them & my letter (to White hall) at mee I took my gloves and left the letter which hee said should not goe.

Sir I pray vindicate my instant cause & the rather because before a number of seamen all strangers told mee I was an old phanattic.

His letter was addressed to the government spymaster Joseph Williamson, and contained intelligence from Grimsby that a large Holland fleet was in sight off Spurn Point. It was a time of mounting war fever: a few days later Charles II formally declared war on the Dutch. Watts resorted to filing his report via Dover, with the postscript ‘Hee said hee would make mee stink at Whitehall.’ Carlile forwarded it to Williamson’s newswriter Henry Muddiman, adding his own view:

I find their is a feud betwixt Mr Watts & Mr Lodge, of Deal, Mr Watts is both honest able & willing to serve his Majestie in his sphear, but the other I think not fitted to be trusted in that imploy he is in, for Lodge was allways factious & Watts was allways loyall, for of the two I think Mr Watts ought to be creditted before the other … I could wish that Mr Williamson would end the contravartion between them & silence Lodge for he is an impertenent fellow.

A week later Morgan Lodge had heard about the complaint; he sniffed that he was falsely accused:

I have all ways demeaned my selfe in my place and station with sociabillity & good respect to all men, & have here to fore both served and suffered for his Majestie & am now a vollenter in Sir Rich. Sands his trup my small estate lay under sequestration … though I am branded by him, who was a sequestrators clarke.

The two men had history. Williamson’s elaborate intelligence network depended on a closed list of informants located around the country, who sent in news and received his manuscript newsletters in return. He kept them loyal without actually paying them by ensuring that the only licensed news sheet, the London Gazette, carried no domestic news worth reading. (By 1666 he had also squeezed out the independent-minded government contractor Muddiman, whose newsletters had provided domestic and foreign news since the Restoration, by cutting his access to government sources and raiding his contact list.)

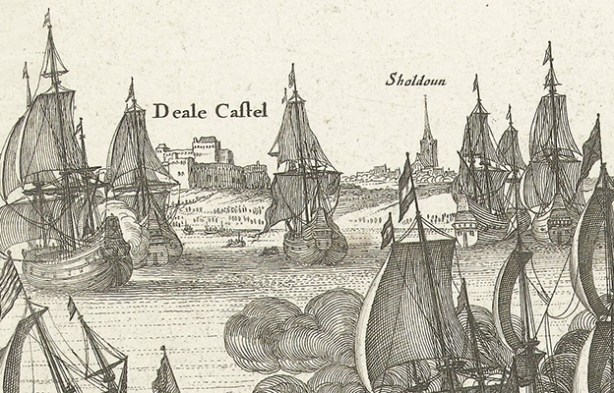

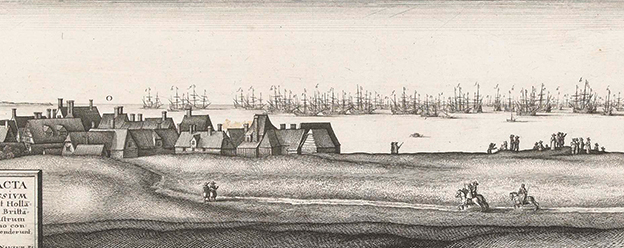

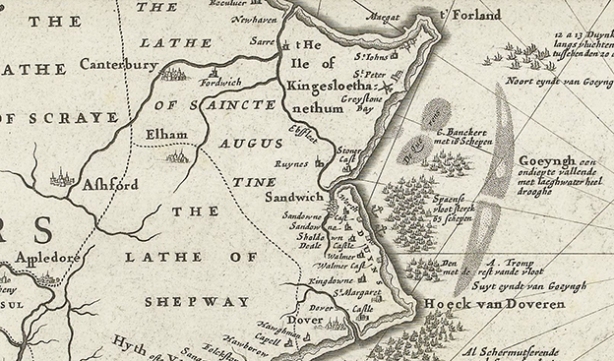

The town of Deal served the anchorage of the Downs, where navy ships were stationed and merchant fleets would pick up pilots for the river, or wait for a following wind or a convoy. Homebound ships put passengers and mail ashore there, to take the faster overland route to London; it was a crucial entry point for intelligence from everywhere. Williamson retained both Watts and Lodge as Deal correspondents; he doubtless took the view that rivalry and fear of being dropped from the privileged circle served to concentrate their minds.

Fear and anxiety extended up the food chain. In 1668 James Hickes, chief clerk at the letter office in London, prostrated himself in a 2 am letter to Williamson: his severe chastisement had sent Hickes from court with tears in his eyes, yet he despaired not of reconcilement when Williamson considered that he was subordinate to the commands of others. He never wrote nor told him an untruth nor declined to serve him, and had suffered great straits in discharging his duty. Hickes’s brief fall from favour gives a flavour of the management style favoured by Williamson, whose portrait by Kneller shows an imperious person with sharp eyes, a pointed nose and a slightly mocking stare.

Who were these two un-notables, postmaster and scrivener, made visible for a while as cogs in secretary Williamson’s intelligence machine? Their lives and activities shed some light on how news was gathered before newspapers were freed from state control.

Richard Watts was born in 1624 near Canterbury, the son of an unfortunate cleric who under Charles I was denounced to archbishop Laud for tavern-haunting and drunkenness, and then accused under Laud’s nemesis Parliament as a delinquent; his property remained sequestered for the rest of his life. Richard Watts had by his own account been in the service of the late king in the Civil War and so had been obliged to go abroad for a while; however by 1660 he had ‘for severall yeares past been imployed in the making of writeings att Deale’. By the following year he was recording tenancies for archbishop Juxon, and later petitioned for a notary’s licence, on the grounds that for the want of a public notary ‘there is a great hinderance to merchants and masters of shipps comeing into the Downes (sometimes to the loss of a fayr wind)’. He got his licence in January 1662, and another as a schoolmaster a few weeks later, both granted by the diocesan court of Canterbury. That year the commissioners for regulating corporations certified that he had suffered much for loyalty and was suitable for an employment of trust. His loyalist credentials were secure.

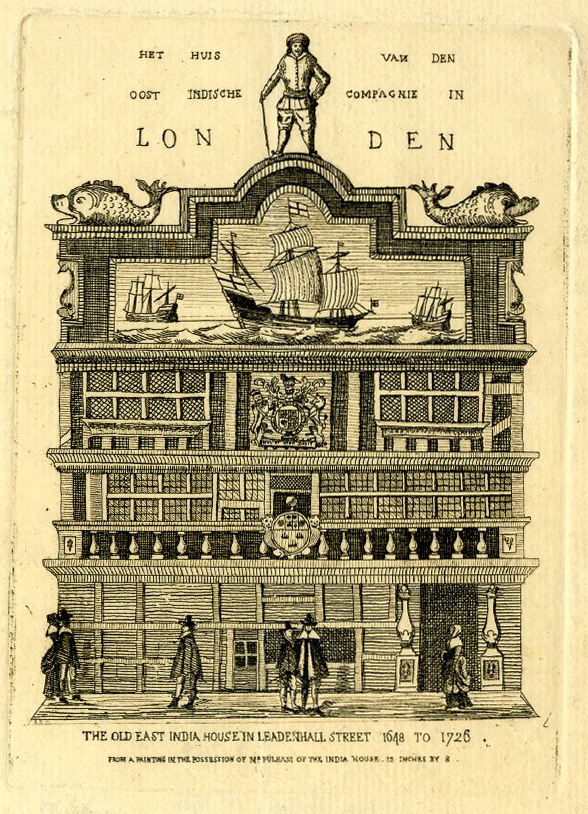

Morgan Lodge was born about 1633, the son of a Somerset husbandman. It is not clear what brought him to Kent, or when he arrived there. His ‘small estate’, sequestered until the Restoration, may have been his late father’s tenement at Chiselborough. There is no sign of Lodge himself in records of sequestered delinquents in either county, although his kinsman John Wills of Chiselborough does appear, having compounded in 1653 – that is, he paid the fee to discharge his estate from sequestration. By 1661 he was living in Deal, and the following year he was licensed as a surgeon – under yet another of the archbishop’s powers – which suggests skills acquired in the military, or perhaps with the East India Company. His route out of Somerset probably had something to do with the Phelips family of Montacute, three miles from Chiselborough.

Robert Phelips and his brother Edward were royalist colonels involved in Charles Stuart’s escape from England after the battle of Worcester. Robert became one of Charles’s courtiers in exile and was closely associated with another of them, the versatile Sir John Mennes, who grew up in Sandwich a couple of miles from Deal. Mennes was an admiral, a secret agent (in a rare sighting he is sent to Flushing to monitor the posts) and also apparently an amateur venereologist who acted as physician to the exiled court. From these circumstances we could speculate – not very wildly – that the young Lodge was caught up in the royalist flight from the south-west, perhaps as a cavalry trooper, and settled in Deal because it was a convenient landing-place for furtive cross-channel travellers: he could be useful there to the royalists. Or maybe he simply found work in that busy place.

Lower Deal was a settlement by the beach made up of houses thrown up ad-hoc during or after the first Anglo-Dutch war by the pilots and other local people who serviced the ships in the Downs, on waste land seized by Parliament from the see of Canterbury. The inhabitants got their living from the fleets, but they were no more compliant with Cromwell’s government than they had to be. After the war, it was reported, a navy captain trying to press a young man at Deal was assailed by a tumultuous company of the inhabitants, and forced with his men to take to the boat, and repair on board, where he was confined several days, both his eyes being injured with stones; all his company were hurt. (The town was no more obliging to Charles II’s pressgangs ten years later.) Pilots refused to serve in the English men-of-war, and the chief surgeon at Deal reported that local people caring for sick and wounded seamen would take no more in; in both cases for want of payment by the admiralty.

Lodge had a god-daughter, Edith Blake, whose father was an ironmonger at Langport on the Somerset Levels; she later married Robert Phelips’s nephew Sir Edward Phelips. Her birth around 1663 suggests her godfather Lodge was in Somerset that year, possibly to see to his lost property, although he was by then living in Deal. At his death he bequeathed to her ‘one candle cup and two trenchers and plates of silver that have the Phillips armes on them two yards of cloath of silver and half or thereabouts and the East India cabinett and the closset of china’; he did not say how these things came to be in his hands. He had a lease on a pair of inns in Lower Deal called the East India Arms and the Mermaid, the latter perhaps honouring the celebrated Mermaid tavern in Bread Street, London, destroyed in the fire. The Phelips silverware and East India cabinet might have been kept at the East India Arms for the entertainment of the company’s grandees when they came ashore at Deal.

The position of postmaster at Deal was probably Lodge’s reward for service during the Interregnum (one of Charles’s spies, Daniell O’Neill, became postmaster-general in 1663). It was a lucrative position. He was paid to run the post office, to maintain a boat and pay boatmen, and to keep horses and pay postboys to carry the mail. It was usual for postmasters to be innkeepers too, and they had a monopoly of hiring out horses to travellers on the post roads. Watts was among the first to take new leases in 1661 after the Deal estates were restored to the archbishop, on a tenement in the ‘sea valley’ behind the beach.

Under Williamson’s system, in all weathers so long as a boat could be got off Deal beach, a post-office man would tour the ships and collect from each the name, commander, where sailing for or arrived from, and any shipping intelligences they might have picked up. The resulting lists were carried overnight in the mails to the General Post Office in London, on horseback in 20-mile relays by post-boys employed by the local postmasters. The ship lists went to the two secretaries of state, to the navy office and to the custom house; letters from informants went to Williamson, along with covert correspondence from his spies and copies of any letters between persons of interest, which were quietly opened and resealed at the Post Office with an ingenuity much admired elsewhere: ‘They have tricks to open letters more skilfully than anywhere else in the world’ was the view of a French ambassador (quoted in The Intelligence of the Secretaries of State by Peter Fraser, a study of Williamson’s various surveillance operations which resonates now).

Back to the fracas in Deal. The factious Lodge was linked to diehard royalists of the Knights of the Royal Oak, who were resistant to the general mood of reconciliation that prevailed after 1660. Watts’s sympathies were more demotic. In March 1665 there was a complaint from five sea-captains who were searching for seamen hiding in Deal in order to press them. They applied to the town’s chief magistrate for assistance: he was in bed and would not get up, and the other magistrates also refused to help, Watts being one of them. However, he was rattled enough by Lodge’s attack to launch a poisonous assault in his own defence. In April he sent Williamson a list of schismatics in Deal, starting with Samuel Taverner, the former commander of Deal castle who became a Baptist preacher, and continuing:

Salsbury & one Thomas : two foolish Quakers

William Hollis : A rye neckt Anabaptist, hee hath neither wit nor money but an evill heart

John Milford : A good scholler, a cunning fellow an excomunicated Anabaptist, hee is but poore, hee is followed by all the anabaptists & independents in the cuntry. This is hee who is Lodge the postmasters clark, for Lodge cannot write a legible hand. Hee hath the view of outward letters severall houres before wee see them.

The wife of Mr Richard Bridges : hee is a good Christian but his wife worse than a divill against the Cavaldry: shee hath store of money and her husband would bee glad shee were punished, for he cannot beat religion into her, nor pswade her to see a steeple house (As disgracefully they call it)

Knot : A poore Sysmatick

Mr Biglestone : This fellow and his wife very divelish against the Cavaldry, His wife is reported to say about 12 yeares agoe, when her hands were all bloudy dresing a pigg these blasphemers words Oh that my hands were in that rebells bloud Charles Stewart. But since his Majestys happy restoration: shee forsweres it & hee cometh to church when hee hath nothing else to doe (hee is rich)

And so on. He added: ‘Those generally are very dangerous persons & onely wayt for opportunity They were all officers in Nolls Armie’.

Both Lodge and Watts survived, nonetheless, as informants to Williamson and recipients of his newsletters. Lodge sent regular ship lists and occasional letters, but he was not a skilled reporter. Watts had a better nose for useful information and he also had good contacts, particularly among the Deal pilots, who picked up news from around the coast and across the Channel. He reported the movements of ships and people through the Downs and Deal, the successes and disasters of navy fleets, privateers and merchantmen, and sometimes foreign news. He added notes on the reliability or otherwise of his sources, often ships’ masters or passengers, occasionally his own contacts abroad. Williamson’s correspondents had instructions to write by every post whether they had news or not, and from time to time Watts padded his letters with local oddities – on one flat news day he wrote that near Deal a step-aunt had beaten a child to death; the coroner found the child died naturally, ‘at which all men admire’.

In the second plague year Watts moved over to Walmer for a while and took to the water, travelling by boat to send news from up and down the coast. He reported day by day on the desperate situation in Deal: the distemper was very violent, sweeping away whole families, and no intercourse was permitted with Deal so letters must be sent by Sandwich. War brought disease again in 1673: smallpox, calenture and pestilential fevers were rife in Deal, caught from sick sailors who were quartered in poor people’s houses. It was thought that if the Commissioners for Sick and Wounded had hired one house and sent nurses, it would have saved the lives of several of the inhabitants and of many more of the sailors. The commissioner for the Kent coast was, as it happened, the diarist John Evelyn. Watts himself seems to have been a martyr to toothache, his difficulty perhaps that to have a tooth pulled would have meant putting himself in the hands of surgeon Lodge. The only traces of Lodge’s practice as a surgeon are two probate accounts showing payments to him for medicine administered to the deceased in their sickness.

As Williamson tightened his grip on the supply of news there was another flurry of suspicion and distrust. In February 1666 Evelyn passed on to Lord Albemarle something he had been told: ‘The persons name is John Braines, in the packett-boate belonging to the post-office, at Deale; who (I am inform’d) being an Anabaptist, and greate friend to all the factious people about that place, is suspected of conveying intelligence, and doing ill offices under the protection of his employment’. And Watts assured Williamson that he would no longer correspond with the ousted Muddiman. He hoped for the surveyor’s or a landwaiter’s place at Deal – Colonel Titus, captain of Deal Castle, and the Archbishop of Canterbury would vouch for him.

As the war with the Dutch wore on into 1667, Watts tried to recruit more correspondents for Williamson, and we get a view of some practicalities of newsgathering. In February he travelled to the south coast and procured a man in Lydd, instructing him to write to the purpose and not complimentally, but the man proved no use and by July he had found an alternative correspondent at New Romney. This recruit would send his letters by Rye all the summer; but in winter no horse could go that way, and there was no flying boat between Rye and Dover, which was 30 miles. It appears that hostilities between Watts and Morgan Lodge had been suspended: they briefed the new man jointly.

On 12 June Watts had news of the naval fiasco in which the Dutch efficiently devastated the English fleet while it was laid up in the Medway. After covering his back he went on to report the volatile popular mood:

I am commanded by you to show you the opinion and report of the country, but if I should write all, I should first request for a pardon, for mouths are now very loose … when we heard the Dutch were gone up the river, and some of our best ships fired by them, and the Royal Charles in their possession, and little or no opposition, the common people, and almost all others ran mad, some crying out we were sold, others that there were traitors in the Council; then the loss of Dunkirk, the dividing of the fleet, the disbanding the army, the non-payment of the seamen, and permitting so many merchant ships to go out of the land, and several other things were called in question. And truly, had not the news suddenly changed, they would undoubtedly have rose and attempted strange things. Amongst the rest, great blame is laid upon the paymasters of the navy; and as our seamen say, (for we have above 300 in the service), his Majesty is abused, for some of our neighbours have stayed two years and eighteen months for their pay, and yet have offered 8s. in the pound for their ticket money, and cannot get it. As it is at and near Deal, it is all the country over.

Watts was at times Customs surveyor, and Lodge a landwaiter. In 1667 Lodge wrote to Williamson that he could only find a few oranges on board three Ostenders, but was sending them to him as a present, knowing they were scarce in London; on the other hand Watts’s habitual gift was a cask of a local speciality, Margate ale. Lodge was sacked as Deal postmaster late in 1674 and worked for a while at the London head office of the East India company, for which he was already acting as agent in Deal; later he was hired by the Hudson’s Bay Company to board their ships and search for smuggled furs. He was back in the post-office compiling the ship lists by July 1676, when he can be found tangling with the postmaster-general Roger Whitley, who writes to him:

Haveing been an old officer I wonder you are so defective in some part of your Duty, as to omit in your lists, some ships newly come in, the merchants are much dissatisfied thereby. Pray faile not to mention all ships whatever, whether Inward or outward bound, whilst they are in the Downes. Alsoe to give us a distinct accompt of the ship letters, by themselves & alwayes to charge the Deale letters, that if the other happen to break loose among them, we may know how to distinguish betwixt them.

Three weeks later Whitley has spotted a more serious offence:

When you writt to me, to desire liberty to send lists to the navy office and custome house, I had not the least thoughts of your intentions of sending them free, therefore I gave consent, but I must desire you to consider the damage I suffer by it: for they allwaies had their lists from the office and paid for them, (which though but small) yet is dayly and amounts to money in the yeare, so that I must desire you either to send the lists to the office, as formerly, or expect to have them charged upon you, for I must not suffer any incroachments, upon the benefits and priveliges of the office … I doubt not, but you understand these things, and hope you have thatt kindnesse for me, as not to use any sinister practices, in your imployment; but rather to study, in all things to promote, the interest of the office, and of [me].

These two, Lodge and Watts, near the bottom of the elaborate pyramid of Stuart patronage, might be seen as forerunners of the people who would do the legwork for the two branches of the coming newspaper business. Lodge the local agent making himself useful to the authorities and the merchant companies, whose regular ship lists became tradeable information; Watts the notary who knew everyone’s business and was clerk to the fellowship of Deal pilots, whose news reports (often first hand) were interspersed with sketches of local affairs. He died in 1685. Lodge relinquished the position of postmaster in about 1689 but was still retained by the Hudson’s Bay Company. He outlived his wife and children; towards the end of his life he married a Phelips widow and went back to Chiselborough, leaving his properties in Deal and Eastry to his nephew Richard Knight.

We have Williamson to thank for the survival of an eclectic record of ordinary affairs alongside the usual matters of state; it stops abruptly at the point when he ceased to be secretary of state early in 1679. He seems to have thrown nothing away, and he preserved his great stash of papers in an archive which has survived among the state papers of the time. By the 1690s, the pomp of the Stuarts was gone, as was the Licensing of the Press act, two rival London newspapers appeared – The Post Boy and The Flying Post, and a coffee-house keeper by the name of Edward Lloyd was putting ship lists into print as a service to his merchant customers.

One more thing: Morgan Lodge owned a slave. In his will of 1695 he bequeathed to John Wills of Chiselborough ‘the Indian maid that now lives with him’.

Sources

Direct quotations from the Deal correspondence are from letters held in the State Papers Domestic, SP 29, at the National Archives, Kew; transcriptions are mine or, in one case, by the editor of one of the Calendars of State Papers,which are the sources of all the indirect quotations. Extracts from Roger Whitley’s letters to Morgan Lodge are from a Whitley letter book at the British Postal Museum & Archive, POST 94/16. Other source documents are held by Lambeth Palace Library, Canterbury Cathedral Archives, Kent History and Library Centre, Somerset Archive and Record Service, and the British Library.

Pingback: How they broke the chain at Chatham | Things turned up

Pingback: Day-trip to Margate | Things turned up

Pingback: The truth about Margate ale | Things turned up